The eleven year U.S.–Mexico Border Project includes the Anti-Archive—over 867 objects, 30,000 photographic images and over 15 site-specific actions and interventions in the Rio Grande Valley, Texas. Field-work for the project also includes interviews with border-crossers and community members in Texas and North Carolina. This work touches on many topics including gender, immigration, and migration, and rethinks the ways in which we look at diversity, identity, and difference. It presents a new way to look at immigration, a topic that has been understood largely through media and popular culture. It demonstrates the continuous flow of individuals across our southern border and the role of nationhood and state power over this transitional space. The objects seen by many as waste left along the banks of the Rio Grande make meaning when reinterpreted as part of the archive and help us understand borders, belonging, and migration in new ways.

This work has been exhibited at the Baltimore Museum of Art, Maryland, Flanders Art Gallery, Raleigh, North Carolina, LaStellina Arte Contemporane, Rome, Italy, the Nasher Museum of Art, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina, and the Weatherspoon Museum of Art, Greensboro, North Carolina.

Zone of Contention, Weatherspoon Museum of Art, Greensboro, North Carolina, 2012

Objects from the Borderlands, Greensboro Project Space, Greensboro, North Carolina, 2016

Objects from the Borderlands, Greensboro Project Space, Greensboro, North Carolina, 2016

Pedro Lasch, Susan Harbage Page and Yinka Shonibare, The Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, North Carolina, 2013

Pedro Lasch, Susan Harbage Page and Yinka Shonibare, The Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, North Carolina, 2013

The Border Project, Flanders Art Gallery, Raleigh, North Carolina, 2011

The Border Project, Flanders Art Gallery, Raleigh, North Carolina, 2011

Catalogues:

Objects in the Landscape and the Anti-Archive

(2007-Present)

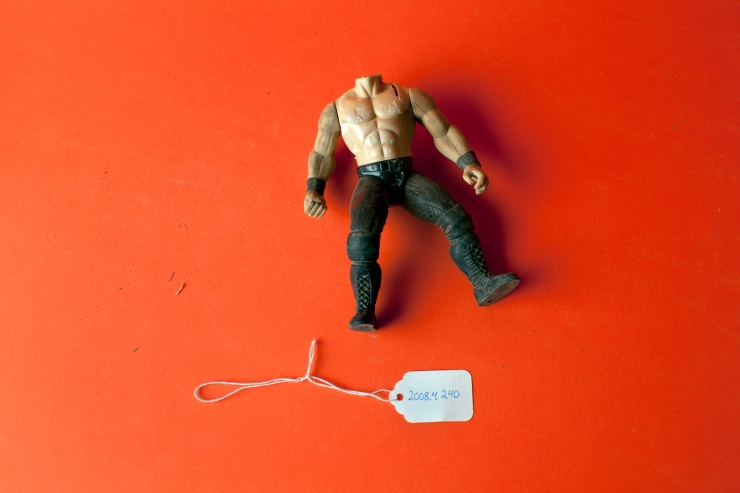

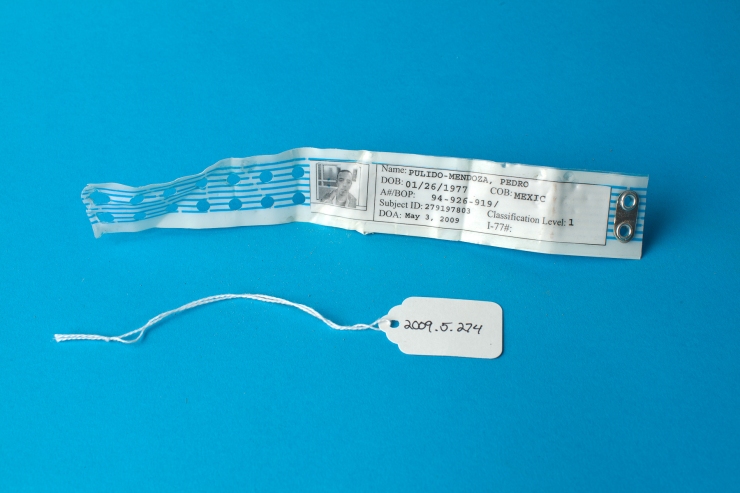

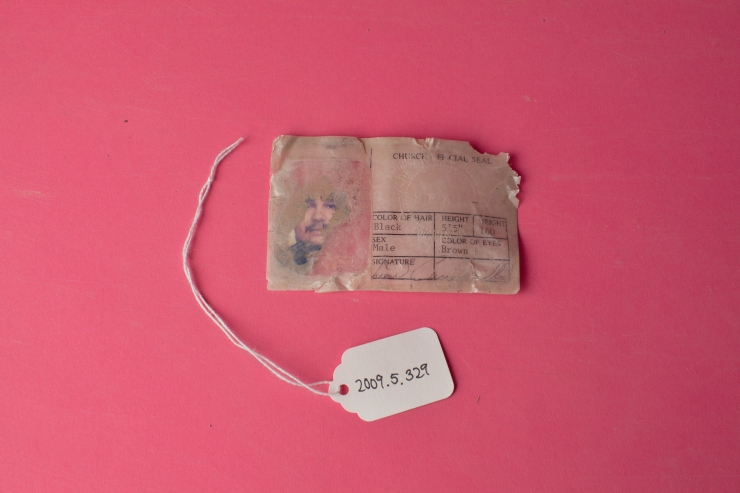

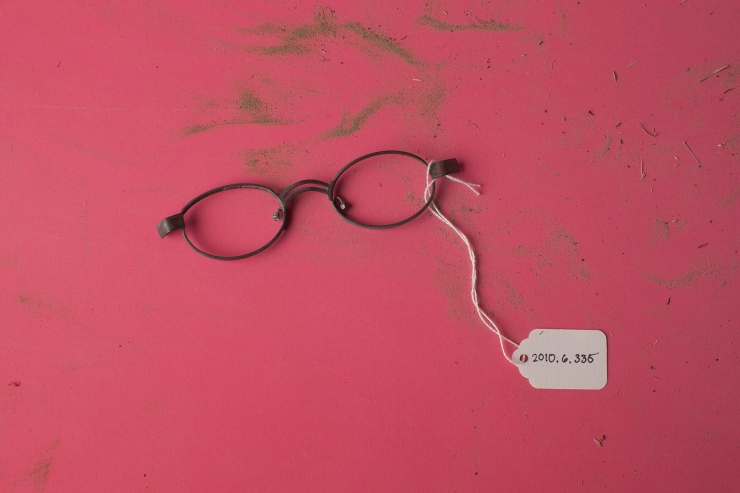

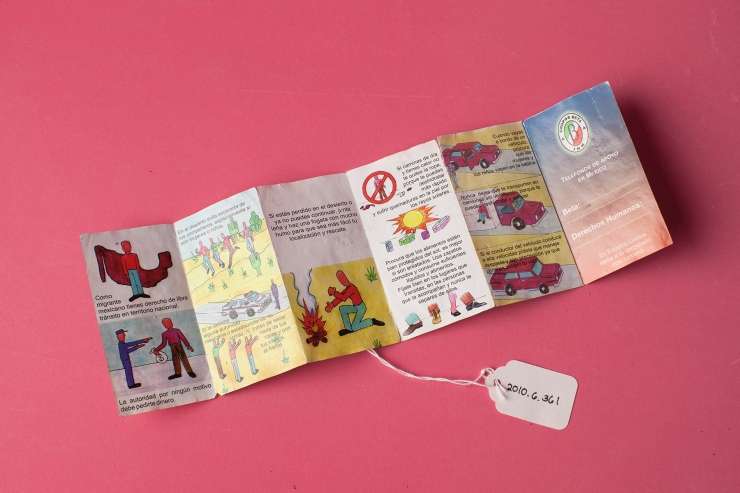

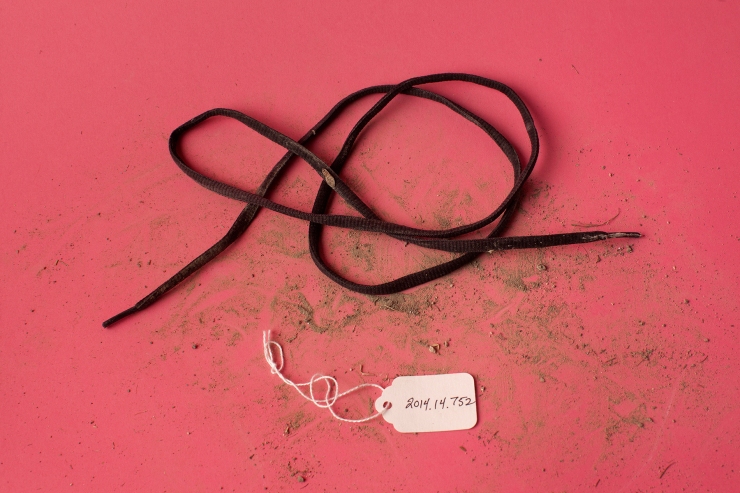

Since 2007, I have been making yearly trips/pilgrimages to walk the border and photograph objects left behind by undocumented migrants crossing the U.S–Mexico border between Matamoros, Mexico, and Brownsville, Texas. My work takes an ever-evolving imagined space and concretizes it as a collection of specific objects, first as they are found and photographed in the landscape, then as they are re-photographed (colorful backdrops counter the implication that they are evidence) and archived, and, finally, as they are united in exhibitions. The documentation of the depersonalized objects and photographs gathered over time become a new way to look at the militarization of the border and the ways in which the power of nations plays out in this contested space. In the end, it represents the fact that some people have access and others don’t. The objects I examine all have incomplete and layered narratives attached to them—for example, when a bra is found placed in a tree, it is said that a coyote (person who smuggles people across the U.S.–Mexico border) has placed it there as a sign that a woman has been raped. Barbara Sostaito writes in Feministing.Com:

But unfortunately, geopolitics can make that most natural border crossing extremely dangerous, particularly for women. A bra can remind us how treacherous the crossing can be. Bras found hanging from trees, the artist notes, are supposedly left by coyotes to mark that a woman had been raped there, sadly a very common occurrence. According to a 2014 Fusion Investigation, 80% of Central American girls and women crossing Mexico en route to the United States are raped. In fact, the threat of rape is so prevalent that many women migrants receive preventative contraceptive injections before embarking on their journey. Women are not only extremely likely to experience sexual assault, they are also more likely than men to die during their migratory journeys, due in part to sexism on the part of coyotes, who are quick to abandon women and children when they can’t keep up. Pregnant women are even more at risk.

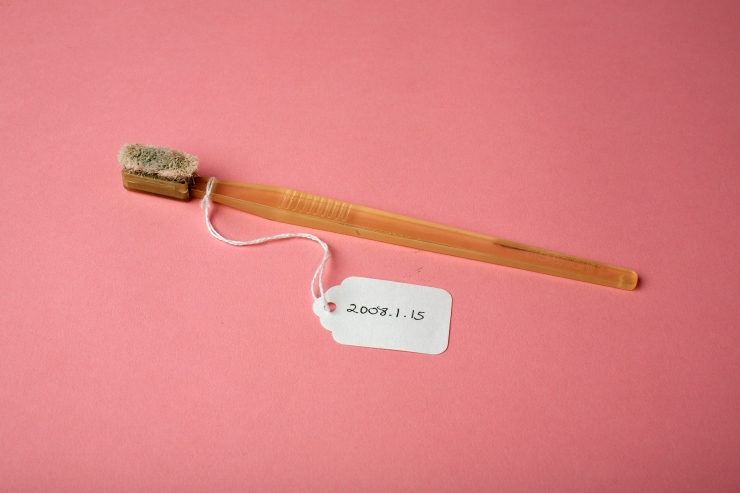

Other objects, such as lipstick, eye shadow, or a man’s razor, offer stories of self-care, normalcy, or someone trying to “fit in” after they have crossed the Rio Grande on a black inner tube and changed into dry clothes before possibly being taken to a safe house in Brownsville or McAllen, Texas. A found comb or toothbrush is a sure sign that someone has been picked up by the Border Patrol (anything short and hard is seen as a potential weapon). These present-day archeological artifacts reflect incomplete narratives and a history of flight, surveillance, and fear. We usually celebrate our histories through the objects saved and owned by the privileged. The Anti-Archive resists tradition by saving and archiving objects left behind by anonymous immigrants coming into the U.S. from Mexico.

Objects in the Landscape

The Anti-Archive

Interventions and Performances

I have completed a series of yearly site-specific art interventions along the border in the Rio Grande Valley, Texas (2009-2015). All interventions were sponsored by Galeria 409, Brownsville, Texas.

Crossing Over: A Floating Intervention (2009)

My first site-specific project was a community-based action, Crossing Over: A Floating Intervention, which protested the proposed building of the border fence in Brownsville, Texas. Working with a group of artists from Brownsville, Texas and Matamoros, Mexico, we created a temporary floating bridge made of children’s inner tubes that united Mexico and the United States underneath the Gateway International Bridge. Using found materials we created a welcome table and gave away swimming, running, and canoeing trophies to border crossers.

Loss: Something of Value, Brownsville, Texas (2010)

In Loss: Something of Value, I placed an oversized corona/wreath on the Border Fence to call attention to the losses that take place along the border—familial, cultural, economic, and personal, including the loss of life. The construction of the 8′ x 8′ corona/wreath was based on a wreath found in a local cemetery and created using traditional materials, processes, and colors.

Blue Circle Intervention, Laredo and Brownsville, Texas (2011)

When I walk the border I invite friends from the area to walk, bike, or canoe with me. I give them a border tour of sorts, showing them the objects and the well-worn paths leading away from the riverbanks to nearby hiding spots and roads. After our pilgrimages, they often comment that their understanding of the border has shifted. What they thought was trash they now see as the remnants of people’s lives, representing hope, flight, panic, and fear. Once they see it, they will always see it. In Blue Circle Intervention, instead of picking up the objects, I left them in the landscape and drew a protective blue chalk line around them, making them visible to passersby.

Humanizing the Border (2012-Present)

Thinking about how borders are demarcated and visualized as a straight line on many maps—often put in place by a group of men negotiating political power in an isolated room far away from the actual terrain—prompted me to photograph my body as the border in the Humanizing the Border series. I began this series of actions by lying down in the middle of the Progresso–Nuevo Progress Bridge, placing my body in precise alignment with the international borderline. The intent was to shift the idea of border from an abstract concept to a concrete humanness related to the body. Borders do not just separate ideas, economies, and products but have very real effects on people’s lives, separating them from family members, important healthcare, safe places to live and jobs to support their families.

My prone, vulnerable, protesting body was dwarfed by a constructed representation of border (seven regimented rows of yellow dots indicating caution and danger) in the first action on the Progresso–Nuevo Progress Bridge between the U.S. and Mexico. I obstructed traffic, was almost hit by a car that hadn’t seen me, and was eventually chased away by the U.S. Border Patrol. The river, over which my living breathing body rested, traditionally a waterway where people come together, becomes through the creation of nations a liminal threshold of separation.

I continued the series on the riverbanks, fields and levees along the border each year. My prone body in a position of passive resistance emphasizes the scale of the border fences and gates, and the immense natural landscape that is the border.

My latest versions of these actions have addressed global borders and migration in the Negev Desert, Israel/West Bank and the Austrian/Italian border

My Mother’s Teacups (2012)

My Mother’s Teacups explores immigration via my own English ancestry. By photographing family heirlooms—teacups my mother brought from England to Ohio in 1969 and then to North Carolina when my family migrated South—along the banks of the Rio Grande near McAllen, Texas, I addressed my own and other U.S. citizens’ history of immigration. The teacups inherently symbolize and embody issues of race, class, heritage, mobility, and nationality. They question the willingness of individuals to lay claim to U.S. citizenship and privilege, disregarding their family’s immigration from other countries such as Italy, Ireland, or Poland just two or three generations ago.

Mirrors on the Progresso–Nuevo Progresso Bridge (2012)

Mirrors on the Progresso asks questions about belonging: where we fit in, where we see ourselves, and what meaning that makes. What should be the basis of citizenship and who should make that decision, you or someone else? Should one’s ancestry, one’s birthplace, or one’s sense of belonging define citizenship? Should we be able to cross boundaries freely or not? I placed mirrors on the international boundary line in the middle of the Progresso–Nuevo Progresso Bridge and watched. People saw themselves reflected in the mirrors I placed over the durable and official brass plaque that declared the exact border of the United States of America and Mexico.

Border as Backdrop (2014)

To help me think conceptually about the border as backdrop for politicians I set up a gray backdrop typically used for portraiture at several sites along the border. Often a photo opportunity for ambitious politicians, the border is reduced to a prop or distorted to a menace, without regard to the people and the economic and sociopolitical realities of the place.

This project intended to question how the border would be seen as we led up to the 2016 elections. My prediction was that immigration, labor, border economics, deportation, detention centers, militarization and surveillance issues would be in the news, and the border again would be used to gain political power and voters. My images emphasize not what has been put in front of the backdrop by popular media outlets, but what is to the left of it, the right of it, far behind it? I purposefully leave it empty so the viewer is drawn to see the everyday space and landscape that is normally undifferentiated on our miniaturized backlit phone and computer screens. The politicians who would usually be center stage are absent.

Sewn Border (2014) and Erased Border (2014)

I produced two art videos about humanizing the U.S.–Mexico border: Sewn Border where I literally sew politics into geography via a topographical map and Erased Border which returns the border back to an older blurrier state of being as I literally erase a lead/graphite line representing the border where I walk yearly in Brownsville, Texas. The substrate for the performance is a piece of handmade abaca paper selected for its transparent skin-like qualities. The ambient audio recorded during the action is important in these pieces and is meant to be loud and somewhat dissonant.

Sewn Border

Erased Border

Cross the Border: An Art Action (2015)

For my most recent intervention “Cross the Border: An Art Action (2015)” Brownsville, Texas I spent eight hours continually walking back and forth across the “official border crossing” on the International Gateway Bridge between Matamoros, Mexico and Brownsville, Texas. This action was asking why information, technology, goods, and culture pass freely over borders, but bodies cannot. Why must thousands of people annually put their bodies at great risk to walk the same path I walk easily, in an attempt to be safe, provide for their families, and simply belong?

Here/There (2016)

In “Here/There,” I photographed myself holding a series of signs at the border wall and on the banks of the Rio Grande/Rio Bravo in Brownsville, Texas. The signs called attention to the issues and divisions that borders create: here/there, us/them, belonging/non-belonging, access/non-access, safety/non-safety. In this image I hold up the sign “Here” while my foot is holding down the sign that says “There”. This can be read as a metaphor, if you hold someone or some country in place, your country and personhood is also held in place.

Crossing Over: Embodied Text (2016)

Crossing Over: Embodied Text is a small installation, which includes sound. I installed it for the first time in the exhibition “Objects from the Borderlands: The U.S. Mexico Anti-Archive,” at Greensboro Project Space presented by the National Folk Festival, Greensboro, North Carolina (2016). It consists of edited audio interviews of two women who crossed the border, a ribbon text made of excerpts from the interviews, and objects important to the women’s stories, which they brought with them across the border. This work is a new way of presenting difficult, intensely personal interviews —the viewer/listener can hold the words in their hands, giving more weight to each sentence, as voices rise and fall against each other. Two Greensboro women who crossed the US-Mexico border illegally shared their journeys and remembered what objects they brought with them.

<p><a href=”https://vimeo.com/214575014″>Crossing Over: Embodied Text (2016)</a> from <a href=”https://vimeo.com/user22399456″>Susan Harbage Page</a> on <a href=”https://vimeo.com”>Vimeo</a>.</p>